Surgery-free brain stimulation could provide new treatment for dementia

A new form of deep brain stimulation being developed by researchers at Imperial College London offers hope for an alternative treatment option for dementia, without the need for surgery.

Known as temporal interference (TI), the non-invasive method works by delivering electrical fields to the brain through electrodes placed on the patient’s scalp and head.

Using these electrical fields, researchers were able to stimulate an area deep in the brain called the hippocampus, without affecting the surrounding areas – a procedure that until now required surgery to implant electrodes into the brain.

The approach has been successfully trialled with 20 healthy volunteers for the first time by a team at the UK Dementia Research Institute (UK DRI) at Imperial College London and the University of Surrey.

Their initial findings, published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, show that when healthy adults perform a memory task whilst receiving TI stimulation it helped to improve memory function.

Supported by funding from the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre, the team is now conducting a clinical trial in people with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, where they hope TI could be used to improve symptoms of memory loss. Patients have been recruited for the trial through the Imperial Memory Unit at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust.

Dr Nir Grossman, from the Department of Brain Sciences at Imperial College London, who led the work said: “Until now, if we wanted to electrically stimulate structures deep inside the brain, we needed to surgically implant electrodes which of course carries risk for the patient, and can lead to complications.

“With our new technique we have shown for the first time, that it is possible to remotely stimulate specific regions deep within the human brain without the need for surgery. This opens up an entirely new avenue of treatment for brain diseases like Alzheimer’s which affect deep brain structures.”

According to the researchers, this could enable scientists to stimulate different deep brain regions to discover more about their functions and lead to new treatments and therapies.

In the study, researchers first used post-mortem brain measurements to validate that the electric fields could be remotely focused on the hippocampus – a curved structure deep in the brain which plays a critical role in memory and learning.

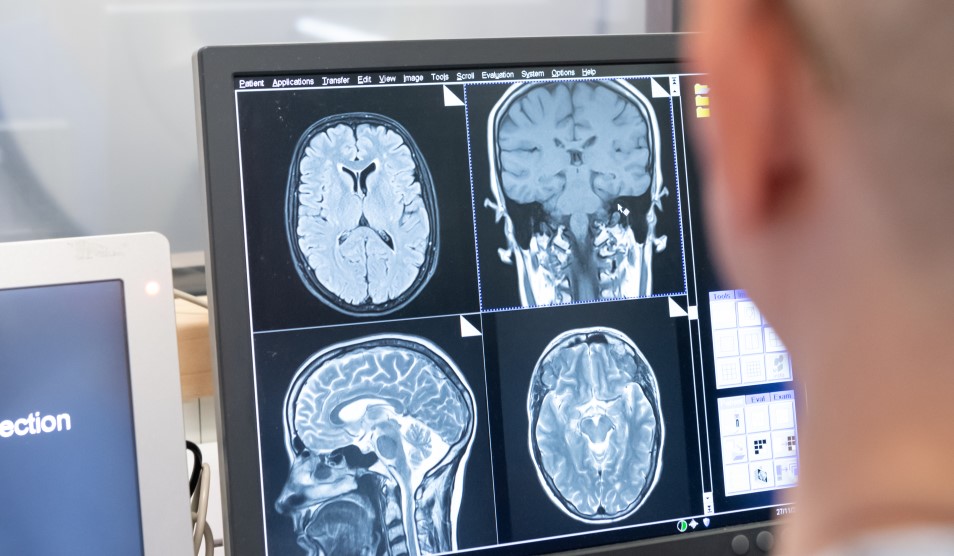

The team then applied the TI stimulation to healthy volunteers while they were memorising pairs of faces and names – a process heavily dependent on the hippocampus. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the researchers showed that the hippocampus was affected by TI during this process. A longer task showed that TI improved memory accuracy.

Dr Grossman added: “We hope this work will help to scale up the availability of deep brain stimulation therapies by drastically reducing cost and risk.

“We are now testing whether repeated treatment with the stimulation over the course of a number of days could benefit people in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. We hope that this will restore normal brain activity in the affected areas, which could improve symptoms of memory impairment.”

This study is published simultaneously with a second paper led by researchers in École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland, which independently validated the technology.

Clinical trials at Imperial College Healthcare are supported by funding from the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre (BRC), a translational research partnership between Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London, which was awarded £95m in 2022 to continue developing new experimental treatments and diagnostics for patients.